How Long Until Alaska’s Next Oil Disaster?

The compromise that passed the Inflation Reduction Act has Alaskans braced for catastrophe.

Stephen Payton has spent a lot of time planning for disaster. The environmental program coordinator for the Seldovia Village Tribe in Southcentral Alaska and a board member of the Seldovia Oil Spill Response Team, he’s helped organize countless drills with volunteers, preparing to respond to an oil spill in nearby Cook Inlet. Over and over, he’s practiced setting out containment booms, floating barriers designed to slow the spread of slicks. But this summer, while drift fishing near the shipping channels in the inlet, he got an up-close view of the oil tankers that could cause such a spill. Their massive hulls dwarf other vessels, casting deep shadows. It was a sobering perspective. “If something were to happen out there—it could just be so detrimental,” he says.

More than 30 years after the devastating Exxon Valdez oil spill, many Alaskans are still haunted by the possibility of another such disaster. Some felt that those fears were about to be realized in 2020, when the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) began preparing to auction off development rights to a million acres of Cook Inlet, a proposal known as Lease Sale 258. Proponents argue that development would eventually buoy the region’s natural-gas supplies, but it would also bring new shipping traffic and an array of new platforms and pipelines to the inlet—along with their associated risks. The Seldovia Village Tribe, other Cook Inlet residents, and concerned people around the country submitted scathing critiques through the public-comment process. The probability that development would lead to another large spill was officially estimated to be one in five; critics argued that the risk was far higher.

In May, the Biden administration canceled the plan, citing a “lack of industry interest.” Though the administration did not explicitly acknowledge the public resistance, opponents felt vindicated. “There was a sense of hope,” says Marissa Wilson, the executive director of the Alaska Marine Conservation Council. “It was like, wow, maybe the public process is working.”

But last summer, Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia insisted that the Inflation Reduction Act include subsidies for fossil-fuel companies and guarantee opportunities for new oil and gas development, including sales in Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico. As a result, Lease Sale 258 was resurrected by a bill intended to protect the climate—leaving Alaskans bracing for catastrophe.

“It was shocking,” Payton says. He has three young children, and he’s teaching them to fish. If the sale is approved, Payton wonders, what will these waters hold when his kids are grown?

East of Cook Inlet, on the other side of the spruce-stubbled Kenai Peninsula, lies Prince William Sound, where the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System ends at an export terminal in a small fishing town called Valdez.

In the 1970s, when a consortium of oil companies began building the 800-mile-long pipeline, many local fishermen objected to the project, concerned about the risks of a spill. As oil started flowing to Valdez, worries about the operation’s oversight intensified. In 1989, a commercial fisherman named Riki Ott testified to a civic group in Valdez, saying, “Fishermen feel that we are playing a game of Russian roulette.”

The next day, the oil-tanker captain Joseph Hazelwood guided the Exxon Valdez and its 53 million gallons of crude oil toward the sea. He found the narrow sound peppered with icebergs, fragments of a quickly deteriorating glacier. Late in the evening, he handed over the helm to an inexperienced third mate, telling him to put the ship on autopilot. (The National Transportation Safety Board later determined that Hazelwood was impaired by alcohol.)

While Hazelwood slept, a crew member noticed that the warning light indicating a shallow reef was on the wrong side of the ship. The Exxon Valdez was off course. “I think we’re in serious trouble,” the third mate told Hazelwood over the intercom. As the captain raced back to the bridge, the Exxon Valdez shuddered and crashed to a halt, its metal hull tearing open on the reef.

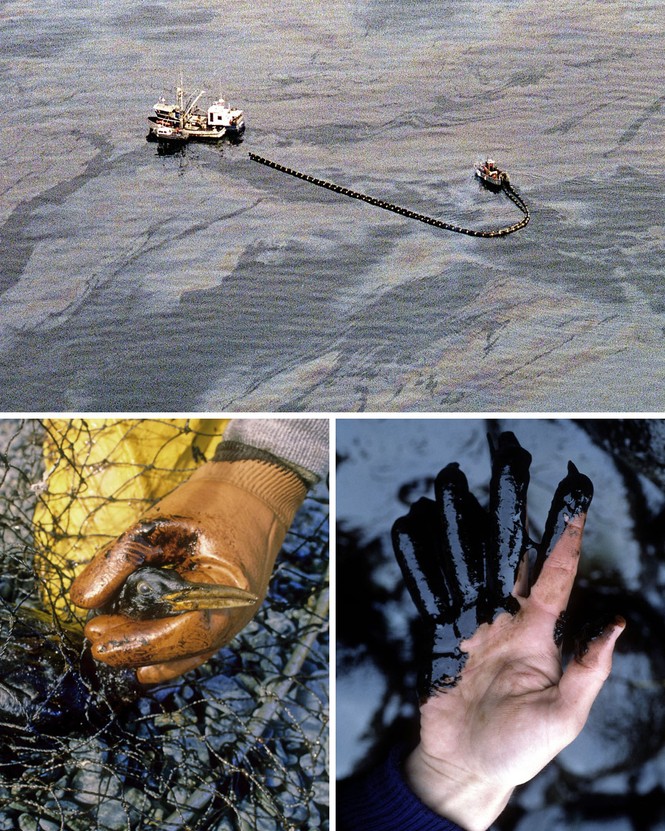

As the snow-covered fjords brightened in the cold spring morning, crude oil gushed into Prince William Sound. When it hit the water, its chemical composition began to change, releasing benzene into the air and transforming into a sticky tar that clung to anything it touched. Craig Matkin, a marine biologist, was working on his boat in the nearby town of Seward. “I walked up the ramp, and I heard the radio at the Coast Guard office,” he recalls. “And I went, ‘Holy shit.’”

Matkin remembers rushing to find emergency booms, hoping the floating barriers would help contain the spreading slick. Then Matkin and his pregnant wife, Olga von Ziegesar, also a marine biologist, set out to find the killer whales they’d spent years studying. Choking on the fumes rising from the water, they found a pod attempting to shelter near an island. As oil swept past, the animals circled in the island’s lee, trying to avoid the slick, von Ziegesar recalls. “But they finally turned, and swam right through it.” In the years after the spill, 15 whales either went missing or were found dead, all but dooming a genetically distinct subpopulation.

While Exxon representatives, state regulators, and federal officials argued about what to do, a storm blew in, making it impossible to break up the oil with chemical dispersants. Instead, gusts of up to 70 knots lashed the spill into a poisonous foam, spreading it hundreds of miles around the peninsula and into Cook Inlet, eventually fouling 3,200 miles of beaches.

With no incident-command system in place, the response soon created its own disruption, and remote coastlines echoed with the chop of helicopters. “Exxon wanted to get every fisherman on the payroll,” Matkin says. After someone photographed his boat towing booms, he says, he found an unsolicited $250,000 check from the company in his mail. Furious, he returned it.

Nancy Yeaton, who is a member of the Native Village of Nanwalek, was one of many Cook Inlet residents who joined a cleanup crew. Exxon offered double the local wage, eventually employing 11,000 people. “We became professional rock wipers,” Yeaton says. “You’d go pick up a rock, wipe the oil off, and look around for another. It was senseless, but at the same time, what could we do?” Crews also conducted high-pressure hot-water washes that essentially boiled the beaches; studies later found that the heat of the water, along with the displacement of oil below the waterline by the force of the spray, only worsened the initial damage.

There was no way to clean the fish, shellfish, and other seafoods that Yeaton’s community depended on, and the loss was especially hard on the elders. “They lived their whole lives on what was given to them from the land and the ocean. Now, all of a sudden, we’re telling them, ‘You can’t eat that because of the oil,’” Yeaton remembers. Losing the tradition of gathering those foods had a big impact, too. “Those were the times that parents spent with their children, gathering and relaying stories and values.”

As the local herring fishery collapsed, Exxon resisted paying damages to residents. The company filed claims against the Coast Guard, arguing that it had been negligent in granting licenses to the company’s crew members and had not provided “adequate navigation services” to the vessel. Fishermen lost their homes and went bankrupt while the cases crawled through the legal system. In 2008, the Supreme Court finally ruled that the company only had to pay $507.5 million of the original $5 billion in damages. An estimated 8,000 of the original plaintiffs died before receiving any compensation.

“Success bred complacency; complacency bred neglect; neglect increased the risk,” an Alaska Oil Spill Commission report concluded. The U.S. Geological Survey, for example, had warned Exxon that a changing climate was causing glaciers to retreat, filling shipping channels with hazardous ice. In sum, the commission wrote, “The wreck of the Exxon Valdez was not an isolated, freak occurrence, but simply one possible (and disastrous) result of policies, habits and practices.”

The herring fishery never recovered. Low-level oil exposure continues to cause heart defects and lower survival rates in salmon. A 2017 study of the peninsula’s beaches found that in some places, subsurface oil residue remains up to eight inches thick.

Of the killer whales photographed swimming through the slick, only one, known to researchers as Egagutak, survived. His family has dwindled to seven elderly members. Because his subpopulation’s calls are so distinctive, researchers are able to recognize his long, mournful wail—a soon-to-be-lost dialect, calling out through an emptier ocean.

In the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez disaster, Congress passed a law requiring oil tankers in U.S. waters to have double hulls by 2015, a move that appears to have reduced the number of spills from shipping. Yet as the industry, in search of new oil and gas deposits, has moved its operations offshore, the risk of other kinds of fossil-fuel disasters has increased. Recent history suggests that in Alaska, neither the federal nor the state government is willing to publicly confront the problem.

Alaska’s offshore oil and gas production began in the Cook Inlet basin around 1960. But by the early 2000s, the production of natural gas from Cook Inlet had long since peaked and was shrinking, sparking concerns about the regional energy supply. So when Hilcorp Energy Company bought Chevron’s aging Cook Inlet assets in 2012 and promised to revitalize offshore production in the area, Alaska officials welcomed the company to the state with open arms. Hilcorp, now the country’s largest privately owned oil and gas company, would become integral to Alaska’s energy industry. Today, a company spokesman says, “Hilcorp is committed to Alaska and looks forward to continuing to responsibly produce Alaskan oil and natural gas, create Alaskan jobs and contribute to the state’s economy for decades to come.”

During its first four years of operations, however, Hilcorp violated state regulations so regularly that the Alaska Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (AOGCC) issued a blunt rebuke, writing that “the disregard for regulatory compliance is endemic to Hilcorp’s approach to its Alaska operations … Hilcorp’s conduct is inexcusable.”

In 2017, a helicopter pilot flying over one of Hilcorp’s Cook Inlet oil platforms noticed bubbles billowing up from a break in a 50-year-old pipeline. The leak wasn’t repaired for more than three months, even though a single day’s leakage could have powered hundreds of homes. (At the time, Hilcorp announced that it had reduced the amount of gas flowing through the line, but said halting production would depressurize the pipeline and increase the chances of an oil spill.)

The chair of the AOGCC, Hollis French, believed that the state had a responsibility to investigate the leak. But he faced resistance from his fellow commission members for months. In January 2019, Governor Mike Dunleavy warned French that he was in danger of being removed from the commission for “neglect of duty.” Less than two weeks after Dunleavy issued this warning, Hilcorp Energy gifted $25,000 to an “independent expenditure group” supporting Dunleavy. French was fired the following month. (Dunleavy’s office did not respond to a request for comment.) French took the pipeline issue to court, and the Supreme Court of Alaska ultimately agreed that the agency had a responsibility to investigate the leak. But the agency continued not to investigate—even as the same pipeline leaked again in 2019 and 2021.

The AOGCC did fine Hilcorp for several other violations of requirements intended to prevent spills and leaks, including two fines totaling $64,000 at the end of 2021. The agency cited “Hilcorp’s lack of good faith” and, again, the company’s “track record of regulatory non-compliance.” (A spokesperson for Hilcorp said at the time that the company “takes seriously AOGCC’s recent orders and is taking proactive measures to ensure similar incidents do not happen in the future, including better contractor management, revising procedures, and dedicating additional resources focused on well integrity.” The AOGCC did not respond to a request for comment.)

Meanwhile, Alaskans have become heavily dependent on Hilcorp for electricity, heating, and transportation fuels: The company not only produces approximately 85 percent of Alaska’s natural gas but also controls much of the state’s energy infrastructure. “Never before in the state’s history has Alaska been so reliant upon a single energy company,” says Philip Wight, a historian who specializes in Arctic studies at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks.

Back in 2012, the Federal Trade Commission raised concerns about Hilcorp’s control of all of the region’s gas storage and the majority of its pipelines. But the FTC deferred to the state, which chose not to take action. “Without competition, regulation, or anti-trust oversight, Hilcorp has been able to demand monopoly rents and anti-competitive contracts for natural gas from Alaskans,” Robin Brena, a longtime oil and gas attorney, said in an email. Hilcorp’s contracts often have anticompetitive features—for example, requiring utilities to sign away their ability to purchase from other vendors in order to work with the company.

In 2020, Hilcorp acquired BP’s nearly 50 percent share in the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System as part of a $5.6 billion deal. The privately owned company did not have to publicly disclose its finances, leaving many Alaskans concerned that it would not be able to operate the pipeline safely or respond to accidents. (In a statement at the time, Hilcorp argued that it was keeping its financial information private to protect its competitive advantage, not because it was avoiding any responsibility to prove that it was “sufficiently well-capitalized.”)

Valdez city officials—well acquainted with how expensive oil accidents can be—were so upset about this lack of transparency that the city appealed the decision of the Regulatory Commission of Alaska that allowed Hilcorp’s financial statements to remain private, arguing that barring access to the documents violated the public’s rights. As one of the attorneys representing Valdez, Brena says the RCA and other state agencies have long failed to enforce transparency requirements for utilities and gas producers, leading to an unregulated market. “Transparency is the key to the establishment of good policy,” Brena says.

Hilcorp recently announced that it might not extend its current contracts with Alaskan utilities, the earliest of which will run out in April 2024. Although the conversations with the state’s newly formed utility working group have not been made public, some of the largest utilities are concerned enough to be exploring the options for importing gas from outside Alaska.

At the same time, Hilcorp is expressing interest in expanding its operations in the state. While the company is known for buying older oil and gas fields and eking out further profits—a strategy sometimes called “acquire and exploit”—a Hilcorp spokesperson recently said the company expects to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on gas production in Cook Inlet in the coming years. Hilcorp recently endorsed a proposal to build a new 800-mile-long natural-gas pipeline that would connect its stranded gas resources on the North Slope to an export terminal in Cook Inlet, opening access to global markets. The Alaska Gasline Development Corporation, a state-owned organization, recently announced an agreement with Hilcorp to assess plans for the export facility. And the president of the corporation, along with Governor Dunleavy, met privately with Hilcorp this summer to discuss the gas supply for such a project.

Because of its dominance in the region, Hilcorp is likely to be the only bidder on the million-acre lease in Cook Inlet—Lease Sale 258, which the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management included in the five-year plan it announced in 2016 and which it began to formally consider in 2020. The agency conducted an analysis of the potential environmental consequences of the sale, known as an environmental impact statement, or EIS, in four months—a radically abbreviated process, considering that EIS analyses often require years to complete. A recent study of EIS analyses by the U.S. Forest Service, one of the few agencies that compile comprehensive data on these reviews, found that they typically take a median of 2.8 years to complete. “It was an impossibly short period to comprehend anything robust enough,” says Josh Wisniewski, a skiff fisherman who lives and works in Cook Inlet. “It felt like a rubber stamp.”

The analysis found that the development of the lease area could lead to the construction of up to 200 miles of pipelines and a marked increase in associated shipping traffic. It also estimated the chance of a large spill over the project’s multi-decade life-span to be roughly one in five.

One problem with the analysis, critics say, is that while it essentially assumes that past spills in the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific are an accurate indication of the risk of future spills in the Gulf of Alaska, conditions in Alaska are vastly different. The platforms and pipelines required to develop the Cook Inlet lease area would be located in waters with much stronger currents, and extreme winter weather. Experts from the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Center for Biological Diversity, among others, say the EIS “presented an incomplete and misleading picture of oil spill impacts and risks based on flawed modeling.” The environmental statistician Susan Lubetkin, of Elemental Statistics, argues that the risk calculation for the new development should also include the dangers posed by existing development in the area. In an independent analysis, she concluded that if the lease area is developed, the overall odds of at least one large spill in Cook Inlet will be more than one in three.

(In an email, a spokesperson for BOEM said the agency “used the best available information in our oil spill risk analysis and has invested considerable time, effort and funding in the past few years to improve the oil spill risk analysis.”)

Many of the protected marine mammals that live in or move through the lease area could be affected by shipping traffic and noise pollution, including humpback, fin, and killer whales, and a critically endangered beluga-whale population that has dwindled to fewer than 300 animals. Even the preliminary steps Hilcorp has taken to explore the area’s potential have had an impact, von Ziegesar says. She recorded the company’s search for underwater fuel deposits in 2019, which entailed weeks of repetitive underwater blasts on the same frequencies whales use to communicate.

The EIS suggests that mitigation measures, such as timing activities seasonally to reduce disturbances, will minimize impacts on marine mammals, and that fish populations will do fine, because “individuals will habituate or leave the area.” But the possibility that species might move to avoid the development noise “doesn’t assuage anyone’s fears,” says Sue Mauger, the science and executive director at Cook Inletkeeper, a community-based organization that works to protect the watershed. “People have invested a lot of time and money on setnet sites based on where fish swim.”

Fisheries in and around the Gulf of Alaska are already struggling to recover from a marine heat wave from 2014 to 2016, nicknamed “the Blob,” which caused mass die-offs of fish and birds and was followed by another destructive marine heat wave in 2019. In 2020, cod numbers in Lower Cook Inlet dropped so precipitously—likely due to the combined effects of warming water temperatures and ocean acidification—that for the first time, the cod-fishing season was canceled. “It’s so poignant that the federal lease sale is in these exact same waters,” Mauger says. The prospect of pumping more oil and gas out of a warming sea, she continues, “is really hard to take.”

BOEM completed its preliminary environmental analysis on the impacts to the region on January 13, 2021, a week before President Donald Trump left office. On January 27, President Joe Biden issued an executive order that paused all new federal oil and gas leases, including the Cook Inlet sale. Thirteen states, including Alaska, filed suit, ultimately prevailing in district court, and in October 2021, BOEM opened its EIS to public comment.

When Hilcorp representatives at a town hall meeting in the Cook Inlet town of Homer suggested that fish populations would simply move away from the disruption, a heckler shouted that the proposition was “total bullshit,” and someone in the crowd blew an air horn. Ninety-three thousand people commented on Lease Sale 258, and according to an analysis by Cook Inletkeeper, more than 99 percent of them opposed its development.

Supporters of the lease, like the lobbying group National Ocean Industries Association, argued that its development would reduce national dependence on foreign energy sources; after Russia invaded Ukraine last February, these energy-security concerns gained new political power. But it often takes a decade for production to begin after a lease sale. Ben Boettger, an energy outreach specialist at the Alaska Public Interest Research Group, points out that according to BOEM estimates, the lease area only has enough gas to meet local needs for approximately four years. “What we’re really running out of is cheap gas,” says Erin McKittrick, speaking as a resident of Seldovia, although she is also on the board of the Homer Electric Association. “Geologically, you can find more gas in Cook Inlet, but how much does it cost?”

In May 2022, the administration canceled the lease sale. While BOEM publicly cited a lack of interest, internal emails suggest that the agency may have run out of time to hold the sale, as its most recent auctions-management plan expired in June. As the salmon runs began this summer, locals who had opposed the sale celebrated.

Now, under the terms that Senator Manchin negotiated in exchange for his pivotal support of the Inflation Reduction Act, the federal government must not only resume the sale but also do so on an accelerated timeline, before the end of 2022. So this fall, BOEM dusted off its EIS, publishing a final version in October.

Lease Sale 258 has traveled an unusual path to approval, but the critiques of its environmental analysis are not unique: While the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act requires the government to assess and disclose the environmental impacts of proposed projects, it doesn’t require agencies to choose the least harmful option. Some people argue that NEPA was intended to be substantive, says Jamie Pleune, who researches environmental law at the University of Utah, but decades of litigation have ensured that “NEPA is simply procedural—all agencies have to do is acknowledge the impact.”

Even strong public opposition may have little or no effect. “People go to comment, and then feel that nobody listens, and I think that’s a legitimate feeling, because it’s true,” says Raúl M. Grijalva, Democratic representative from Arizona and chair of the Natural Resources Committee. Disregard of public input is a long-standing problem; in 1997, a Council on Environmental Quality report found that “agencies sometimes engage in consultation only after a decision has—for all practical purposes—been made.”

In Alaska, this problem is exacerbated by the limited staff and resources of the state’s many small, remote communities, whose residents are frequently the last to know the details of proposed projects. During a flurry of oil and gas development in the 1970s, for example, the Inupiat leader Eben Hopson complained that “EIS reports tend to irritate rather than inform. They commit information overkill. They reveal nothing by talking about everything.” Hopson continued, “They are often inconclusive about the balance of risk to our people and our land.”

During any EIS process, federal agencies are required to initiate government-to-government consultations with tribes whose members or land might be affected. BOEM says it reached out to 11 Alaska Native tribes in Cook Inlet about Lease Sale 258. The only formal governmental consultation the agency conducted was with the Kenaitze Indian Tribe—and only after the tribe called for the meeting. The Kenaitze passed a resolution against the sale, expressing their concerns about the impacts of oil spills and the contribution of the lease area’s development to climate change.

Payton of the Seldovia Village Tribe says that even when the letter of the law is followed, the results can fall short of the law’s intention. Government consultation often occurs belatedly, and tribes don’t always have the administrative capacity to meaningfully participate in these conversations at the last minute. “I don’t know if any letter we’ve ever written has actually had—like, we’ve actually seen anything change in [a] proposal because of it,” Payton says.

The news of the Inflation Reduction Act deal broke in late July, early in the morning Alaska time. “I hadn’t even got out of bed,” Marissa Wilson, the executive director of the Alaska Marine Conservation Council, says. “I just rolled over and saw emails that Cook Inlet had been included to get Manchin’s vote.” She felt physically ill.

It is almost always difficult to draw a direct line between campaign contributions and later actions by political officials. Nevertheless, Hilcorp’s owner, Jeffrey Hildebrand, who has a long history of significant donations to Republican candidates, maxed out the allowable annual individual campaign contributions to Manchin, a conservative Democrat, in August 2021, and hosted significant fundraisers for his reelection campaign. (So far in 2022, Manchin has accepted a total of $735,859 in contributions from the oil and gas industry.) And Lease Sale 258 is one of the few specific federally mandated oil sales included in the Inflation Reduction Act—legislation over which Manchin exercised singular power.

Manchin declined repeated requests for an interview, and in response to a request for a statement, his press team sent the following, which it attributed to the Energy and Natural Resources Committee: “An all-of-the-above approach grants energy producers the confidence they need to invest in American energy by requiring that all remaining lease sales, including lease sale 258, from the previous 5-year program be completed and tying offshore oil and gas leasing to offshore wind leasing.”

In October, BOEM announced its recommendation for Lease Sale 258, called a preferred alternative, which removes several blocks of critical beluga-whale and sea-otter habitat from the lease, reducing it to just under a million acres. It also prohibits seismic surveys during parts of the fishing season. Critics say these are minimal changes that don’t address the lease’s many other risks; the EIS admits that the sale would have “potentially disproportionate adverse impacts” on local communities. “It’s lip service,” Lubetkin says of the changes. “You can have good critiques to the statistical analysis, and have them ignored.” The state of Alaska recently announced an adjacent lease sale that encompasses an additional 2.8 million acres, raising further questions about the cumulative impacts of Lease Sale 258.

Shortly after news of the lease sale’s resurrection broke, local advocates sat down with Amanda Lefton, the director of BOEM. To prepare for the meeting, one of the advocates picked wild blueberries for homemade muffins. Wilson brought a jar of sea salt she’d made from Cook Inlet, “just to try to make that connection.”

Walking in, Wilson was nervous; it was a long shot, but she hoped to talk to someone about the possibility of extending permanent protections to parts of the inlet, as President Barack Obama had done for the northern Bering Sea in 2016.

When the meeting kicked off, she was quickly disappointed. “The basic message was that BOEM’s hands are tied by the congressional mandate,” she says. When it was her turn to speak, she talked about the realities of disaster response on the Alaskan coastline: “There is no way you can stop a spill in the middle of February, when there are 30-foot seas and currents roaring at nine knots—you can’t expect people to risk their lives to go out there and contain what can’t be contained,” she recalls saying. “There’s a reason this landscape is so full of life,” she added, “and that’s exactly why oil and gas exploration should not happen here.”

Wilson remembers the response from Lefton and the other BOEM officials present as subdued; residents were told to keep sharing their concerns and engaging with the process. She left frustrated and upset.

In the days that followed the meeting, the mood among those who had fought the lease was dark. “I’m trying to figure out what to tell our supporters,” Liz Mering, then the advocacy director at Cook Inletkeeper, says. Homer residents have fought to protect Lower Cook Inlet since the 1970s, even successfully raising money through shrimp and crab feeds to help pay for a legal battle that resulted in the state buying back previous oil and gas leases. Cook Inletkeeper itself was formed as part of a settlement for oil companies’ violations of the Clean Water Act—the product of this successful pushback. Now, though, “it’s just like, what do you tell people?” Mering says. “I don’t want to say it’s all meaningless. You want to keep empowering people to take action. But when we just get so ignored …”

Lease Sale 258, now scheduled for Friday, December 30, is happening at a critical moment for the global climate crisis. The window to forestall the worst impacts is rapidly closing, and companies like Hilcorp are part of the problem: A recent report found that Hilcorp is the world’s largest emitter of methane gas, releasing far more of the atmospheric-warming substance than much larger companies. The report’s findings demonstrate that oil and gas producers can take steps to reduce their climate impact; some are simply choosing not to. (Hilcorp told the press that it has reduced its emissions since the report’s analysis, and that its emissions are relatively high because of its strategy of acquiring older companies.)

“We can’t instantly stop using oil and gas,” McKittrick says. “But we should be transitioning away from it as quickly as we can, while using the infrastructure we already have.” The opportunity to do so in Cook Inlet is slipping away, she explains. Even as states like Florida introduce bans on offshore drilling, she says, “the subsidies Alaska has paid to oil and gas companies make it harder for renewable-energy companies to compete.”

A recent National Renewable Energy Laboratory assessment of Alaska’s renewable-energy potential found that the state could shift roughly three-quarters of its energy demand to renewable sources by 2040—and lower electricity prices by doing so. Hilcorp representatives recently told the Cook Inlet Regional Citizens Advisory Council that the company was interested in using the existing platforms in the inlet for tidal-power generation, harnessing the same currents that make new oil drilling so treacherous (as well as potentially saving the company the cost of platform decommissioning). The National Renewable Energy Laboratory found that Cook Inlet represents more than a third of the country’s total tidal-energy potential, though commercial production of tidal energy is still in its infancy. “Oil and gas is not at all the only option,” Cook Inletkeeper’s Mauger says. “If we don’t want to have unlivable landscapes, we don’t have 40 more years to transition to green energy.”

This fall, oblivious to the political churn, the tide continued to rise and fall over the inlet’s stony beaches. The birch blazed yellow along the sandstone bluffs, a shock of color glorious and fleeting. Soon, bare branches were left stark against the sky, framing the retreating glaciers. As the harbor iced over and the sale ticked closer, a coalition of environmental organizations, including Cook Inletkeeper, filed a lawsuit, claiming that Lease Sale 258 violates national environmental-permitting rules by failing to seriously consider less harmful alternatives and misrepresenting the risks. Wilson, for her part, began to brainstorm. “We’re not going to let this happen,” she says. “People will show up and block the boats. I will. This is my home.

“I’m inseparable from this place,” she continues. “And I know I’m not alone in that.”

This story was produced in partnership with the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York.

This story is part of the Atlantic Planet series supported by the HHMI Department of Science Education